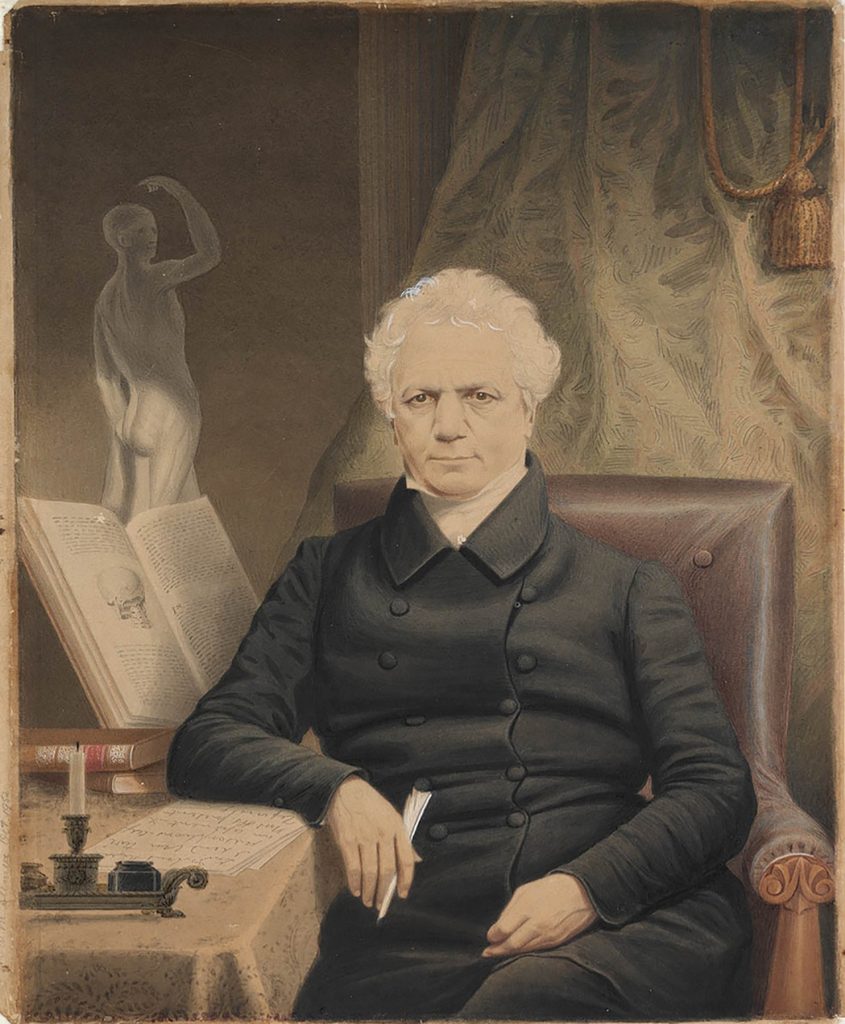

What we see in this image

This right facing ¾ length oil portrait shows Sarah Scarvell, aged 18, posed in a verandah setting, seated on an upholstered [chair or sofa] with an out swept arm, a white [marble or plaster] classically-inspired column with a red curtain drapery behind on the right, and a non-specific landscape view stretching to the horizon on the left. This painting is one of a series of eight known portraits of the Scarvell family by the artist Richard Noble; it may have been painted as a pair to the left facing portrait of her sister, Elizabeth Mary Scarvell (1840-1907) (ML 1195), as both sitters wear very similar dresses – one red and one white.

Sarah’s evening dress is made of a soft, light-weight, gauze-like white fabric arranged in loose pleats across the bodice, or corsage, fanning up from a narrow, pointed waistline into which the full skirt is tightly pleated. The moderately low neckline is cut wide across the shoulders and trimmed with a fine, van-dyke pointed bobbin lace edging, also used on the short, ruched sleeves. The gown is further embellished with wide picot-edged ribbons of pink and gold [shot silk] gauze wrapped around the waist, and tied in bows on each shoulder with floating ends. Sarah also carries a matching gauze scarf [perhaps imported from India] draped behind her waist and twisted around her right forearm. She holds a red rose in her left hand and wears a heavy chain-link bracelet of chased yellow gold on her left forearm, set with a large faceted [citrine] (perhaps a birthstone), and three fine-gauge gold chains around her neck, one suspending a locket.

Her centre parted dark hair is waved naturally, or artificially crimped with heated tongs, looped over her ears and somewhat puffed at the sides, and twisted into a knot at the back of her neck.

The artist has posed the sitter in a very similar manner, and an almost identical setting, to his portrait of the Hon. Mary Caroline Stewart (Mrs Keith Stewart), nee Fitzroy (1823-1895), daughter of Governor Charles Fitzroy (OGH, National Trust, NSW). However, although both women wear remarkably similar gowns, Mrs Stewart’s portrait exhibits a far more overt celebration of the female form better suited to the more worldly and married woman. Mrs Stewart was chatelaine of Government House, Sydney, following the death of her mother Lady Mary Fitzroy at Parramatta in 1847, and her portrait is believed to have been commissioned to mark the occasion of her return to England in 1855.

What we know about this image

Captain John Larking Scarvell (1791-1861) commissioned artist Richard Noble (1806-82) to paint individual portraits of his family in 1855. Noble’s portraits almost invariably reveal a keen interest in the depiction of fabrics, laces and ribbons, as exemplified in this work; all his surviving works are oil paintings, most are signed ‘Richard Noble’ and inscribed with the date and, occasionally, with the place of execution.

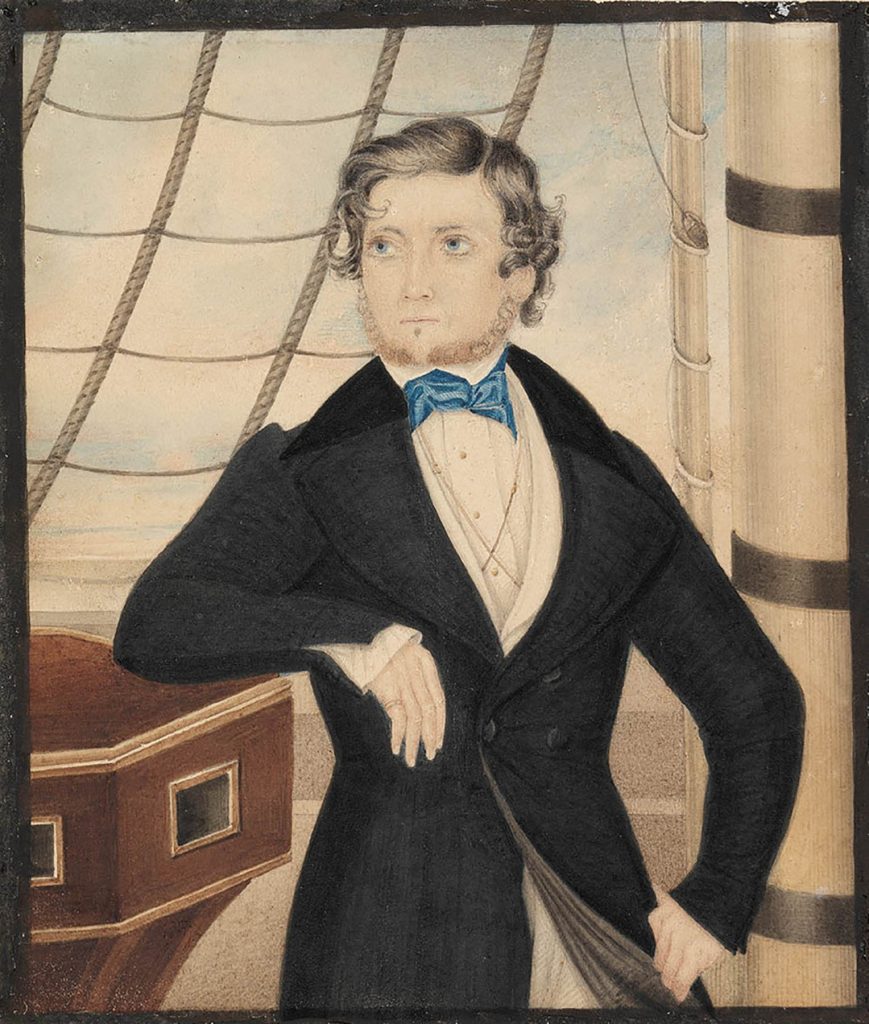

Over the course of the year, while residing at Clare House at Pitt Town near Windsor, NSW, Noble completed portraits of Sarah Winefred Scarvell, nee Redmond (1809-1873) (ML 1251) and John Larking Scarvell (ML 1250), and the six eldest Scarvell children: John Redmond Barnes (1830-1855) (ML 1194); Sidney (1832-1875); George (1834-1877); Edward Augustus (1835-1883); Sarah Winefred Isabella Mary (1837-1929) (ML 1339); and Elizabeth Mary (1840-1907) (ML 1195). According to family tradition, Noble had formed a romantic attachment to Sarah Winifred Isabella Mary Scarvell (then aged eighteen); another family tale is that he had only one arm.

SCARVELL FAMILY:

Sarah Redmond had married John Scarvell at St James’s Church, Sydney, in March 1828. It was the second marriage for Captain Scarvell; his first wife, Isabella (nee Campbell), had died at sea and was buried in St Philip’s Church, Sydney, in January 1828. Scarvell retired from the East India Company shortly after his marriage to Sarah and extended Clare House (previously Killarney) for his family in the late 1820s and 1830s.

The Scarvell family were very close to the Cape family, with several members of each family marrying into the same generation of the other; both the younger Scarvell sisters married Cape brothers – Elizabeth Mary Scarvell to William Frederick Cape in 1863, and Sarah Winefred Isabella Mary Scarvell (1837-1929) to Alfred John Cape in 1871. This portrait later passed to Sarah Scarvell’s daughter, Jessie Cape. At her death in 1963 it passed to Jessie’s niece, from whom it was acquired by the Library in 2004.

ARTIST BIO:

The artist Richard Noble is thought to have arrived in NSW by 1847, though the first documented evidence of his colony career is found early in 1855, when he was commissioned to execute the Scarvell family portraits. He is first listed as an artist in Cox & Co.’s Sydney Post Office Directory for 1857, at 246 George Street. A painter who dealt mainly in portraiture, Noble is known to have exhibited his works in various exhibitions and painted portraits for many of Sydney’s leading residents.

Tue 26 Aug 1856: pleasure of walking round the studio of Mr Noble in George Street, nearly opp. the Post Office…another artist of first-rate talent has taken up his abode among us…though not yet much known here is an artist of considerable European experience, having studied under some of the the most eminent men of is profession in Flanders and the Royal Academy in London.

Following the death of his wife, Harriett, (nee de St Pierre, b. ca. 1835 – d. Nov. 1857), aged 42, of a painful and lingering illness at her residence, Devonshire St, Strawberry Hills, Noble lived in Sydney and Goulburn until 1868, when he returned (disconsolately) to England.

Print page or save as a PDF

Hover on image to zoom in

1855 – Sarah Scarvell

Open in State Library of NSW catalogue

Download Image

| Creator |

| Noble, Richard. P. (fl.1828–1865) |

| Inscription |

| RHS: ‘Rich.d Nobel 1855’ |

| Medium |

| Oil Painting |

| Background |

| To follow |

| Reference |

| Open |