What we see in this image

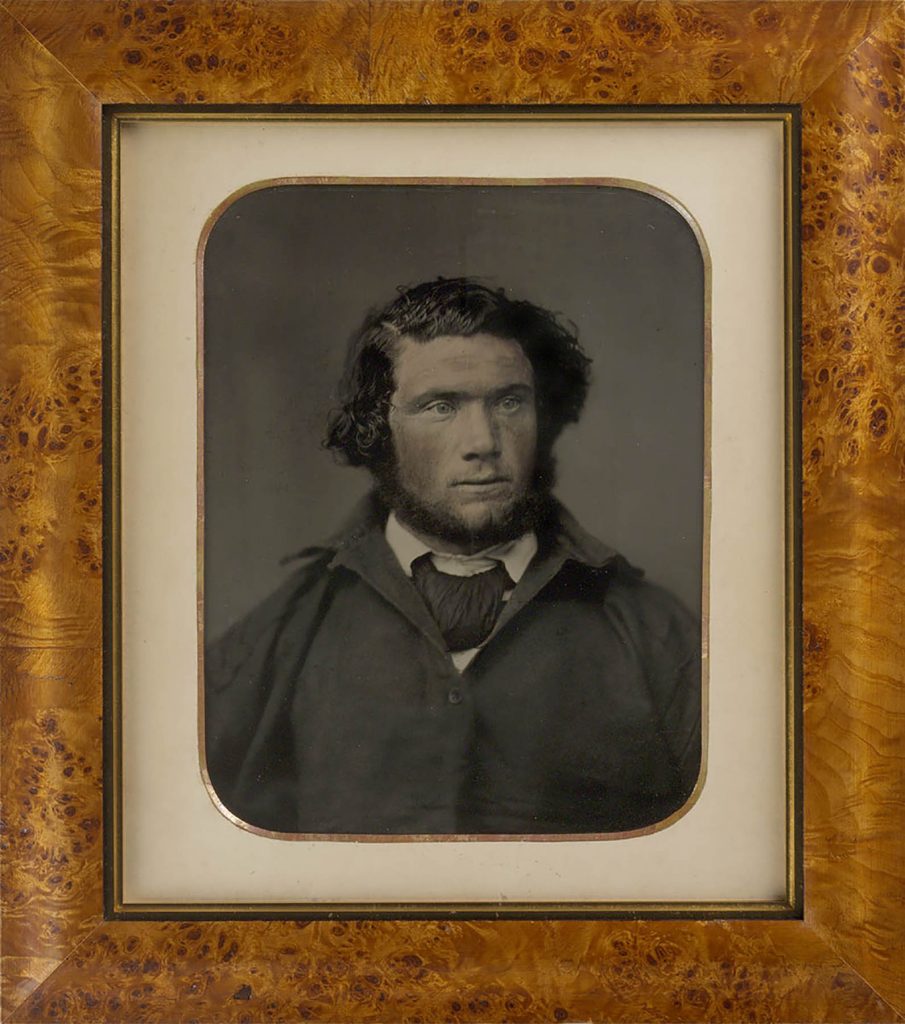

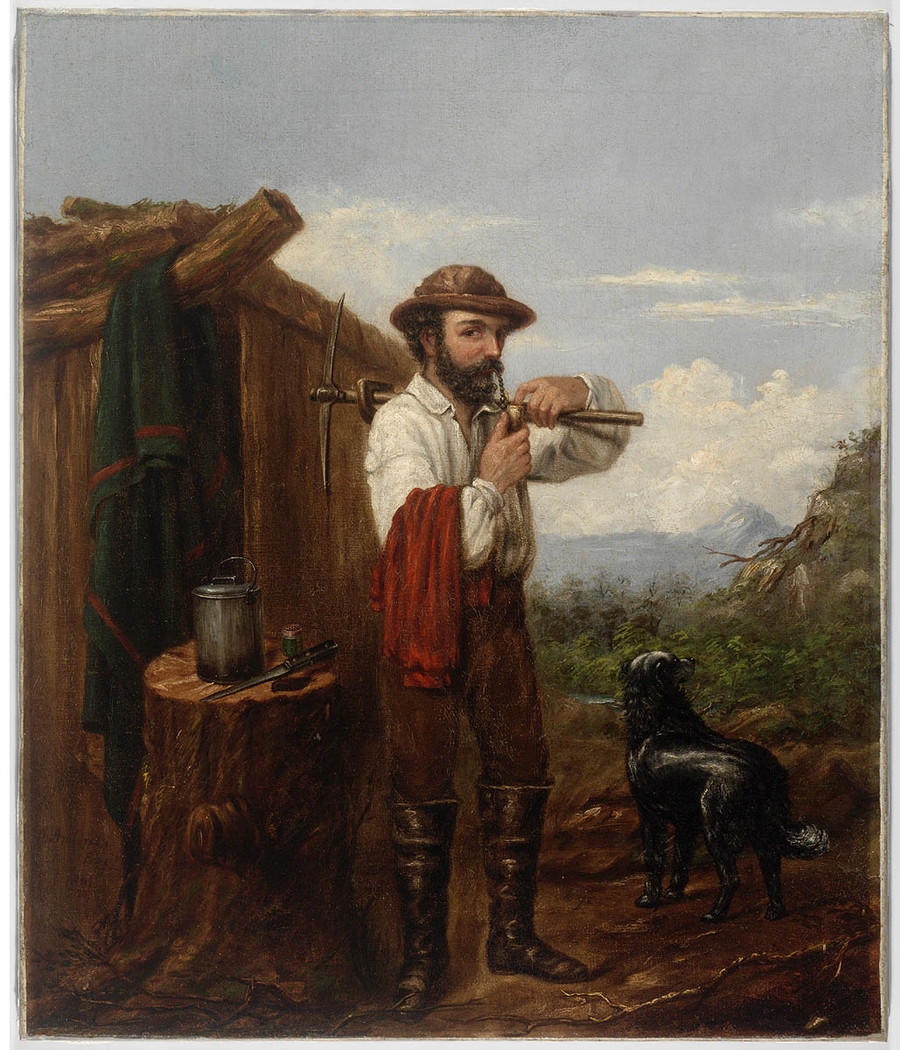

This unusual painting shows an unidentified Australian bushman, probably aged in his thirties and possibly a goldminer, his occupation suggested by the pick and shovel linked together and balanced on his left shoulder. If so, this is an early example of the goldminer subject moving from popular illustration to the more sophisticated genre of oil painting. The bushman is depicted with his [retriever] dog, standing in front of a bark hut with a blanket draped from the ridgepole, next to the stump of a felled tree used as a table set with a billy can, long-bladed knife and [salt cellar or tea caddy], with an Alpen scene stretching to the horizon behind him. He is recorded in the act of tamping tobacco down into the bowl of an ornately carved ‘meerschaum’-style pipe which may indicate his European origins.

The man is dressed in a rather stylised and elegant version of goldfields dress, comprising an unusually spotless and voluminous long-sleeved white shirt left open at the neck and tucked into the waist band of his brown [wool] trousers which are themselves tucked into long brown leather boots extending over the knee. He holds a red flannel ‘Crimean’ shirt over his right arm and wears a light-coloured [cabbage-tree] hat with a low, round crown, covered with a loosely pleated [‘pugaree’], and a narrow brim with a fly veil rolled up at the front. As was the custom in frontier societies, he is unshaven, with a full beard and his dark curly hair left long.

At this time, bushmen and miners wore the type of practical and durable work clothing which had begun to be mass-produced due to increased demand stemming from the California gold rushes (1849-1855) as well as Northern hemisphere conflicts such as the American Civil War (1861-65) and the European ‘Crimean’ War (1853-56). The so-called ‘Crimean’ shirt was a wide, collared V-necked flannel shirt without buttons, the long sleeves of which were rolled up during work.

Popular in solid colours (usually red or blue) and often sashed or belted around the waist, it was often layered for warmth over boldly-patterned striped or checked linen or cotton shirts, and worn with a neckerchief that served as a sweat-rag. Straw hats completed the outfit, light-coloured to reflect the sun and broad-brimmed to shade the miners’ faces.

Australian bush and gold mining life became the principal subject for popular artists such as S.T. Gill and George Lacy, as the notion of Australians as sturdy independent types defined by the bush experience began to take hold during the third quarter of the nineteenth century.

What we know about this image

James Anderson, portrait painter and member of the Royal Hibernian Academy, emigrated from Belfast, Northern Ireland to Australia in 1852-1853. A prolific portrait painter of the mid to late 19th century, this is an unusual painting for Anderson being a genre image rather than the formal portrait of colonel statement and clergy for which he is now mostly known.

Living in Victoria initially, by 1858 Anderson had moved to Sydney, where he continued to paint portraits advertising his studio premises at 389, George-Street in the 1861 Sands Directory of Sydney, and receiving good notices in the local press. (‘..one of the finest specimen of oil painting seen…the likeness unmistakeable whilst the colouring and effect of the painting show the executor to be a finished artist…’, SMH, 17 Mar 1860, p. 5)

In 1861 Anderson was drawn into the controversy over a proposed portrait of the retiring NSW governor, Sir William Denison. While the local committee could not decide on a suitable artist, its members clearly showed a preference for an English portraitist rather than a colonial painter. This prompted the well-known critic Joseph Sheridan Moore to write a pungent letter to the Sydney Morning Herald in January 1861, championing Anderson’s cause and stating that, ‘this “sending home to England” has been the ruin of all efforts to promote high art in its various branches amongst us’. Despite Anderson’s worsening alcoholism, he formed close associations with several professional colleagues, including S.T. Gill (another alcoholic), and continued to receive commissions and produce portraits into the 1870s.

Print page or save as a PDF

Hover on image to zoom in

1861 Goldminer

Open in State Library of NSW catalogue

Download Image

| Creator |

| Anderson, James, fl. 1852-1877 |

| Inscription |

| LHS: signed and dated: “Jms. Anderson / Pinxit / 1861” |

| Medium |

| oil painting |

| Background |

| none |

| Reference |

| Open |